Have a drink with: Napoleon Sarony

Work with me, darling.

Ask him about: Oscar Wilde, cover girl

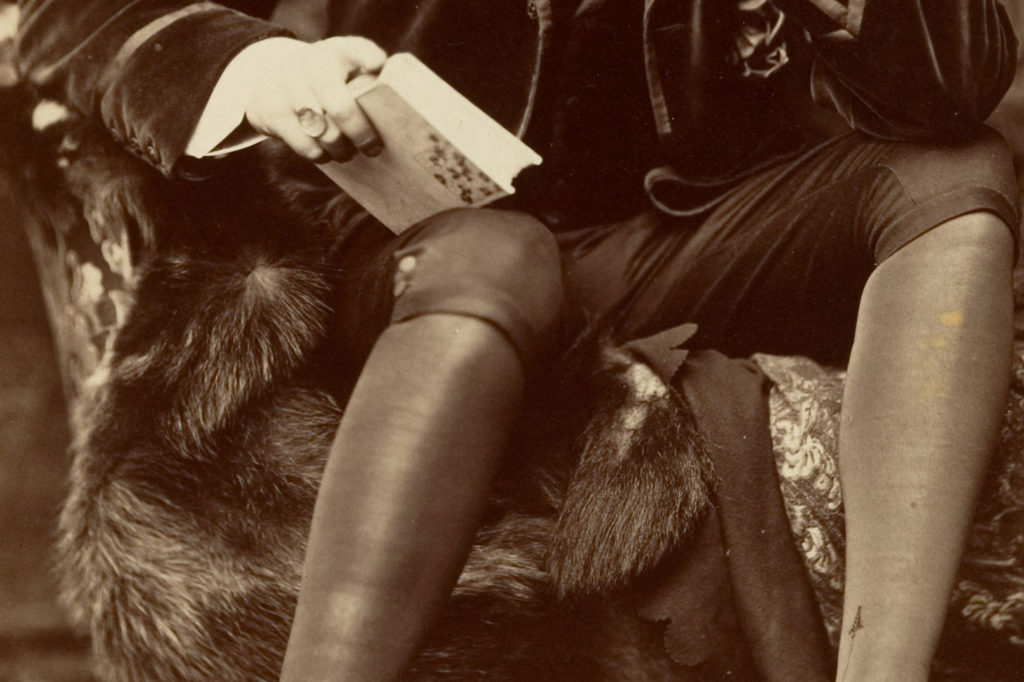

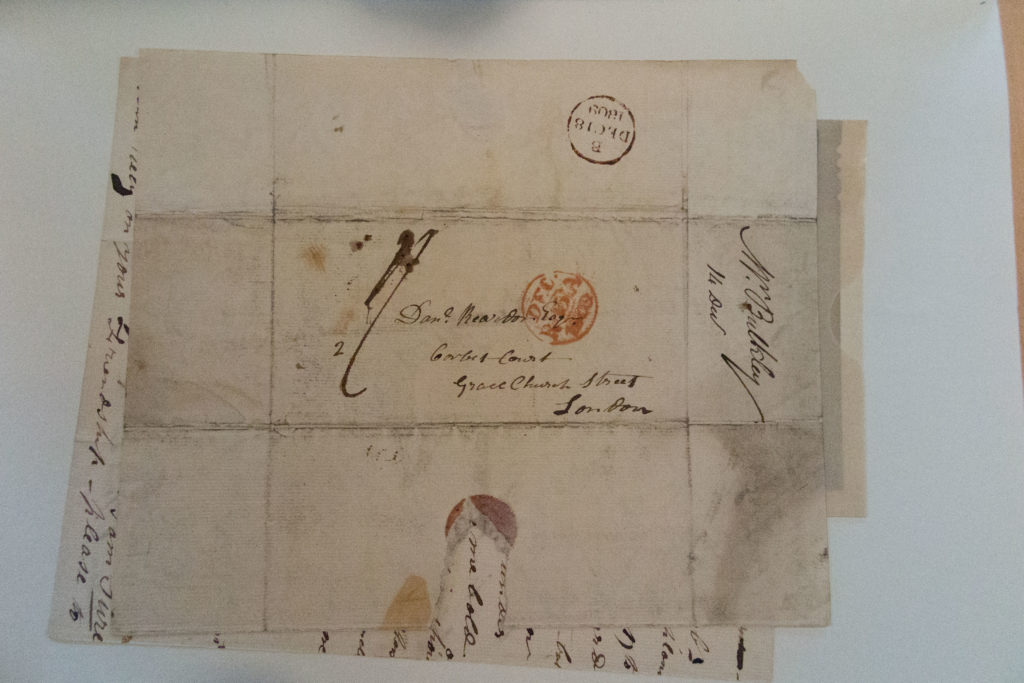

The author of an interview with the photographer Napoleon Sarony, published in the June 1895 edition of Decorator and Furnisher magazine, was clearly excited about getting to meet such a famous figure. In the style of the modern celebrity profile, with luxe asides about the subject’s choice in clothing, food or furniture, the writer gushes that Sarony’s apartment is lavishly decorated, stuffed with Rococo furniture, Latin American pottery, even an Egyptian mummy in its sarcophagus. Fat portfolios of photographs nod to Sarony’s profession, with images of “every known celebrity that has either been born or set foot upon American soil, as well as thousands of photographs of the rank and file of American Democracy.”

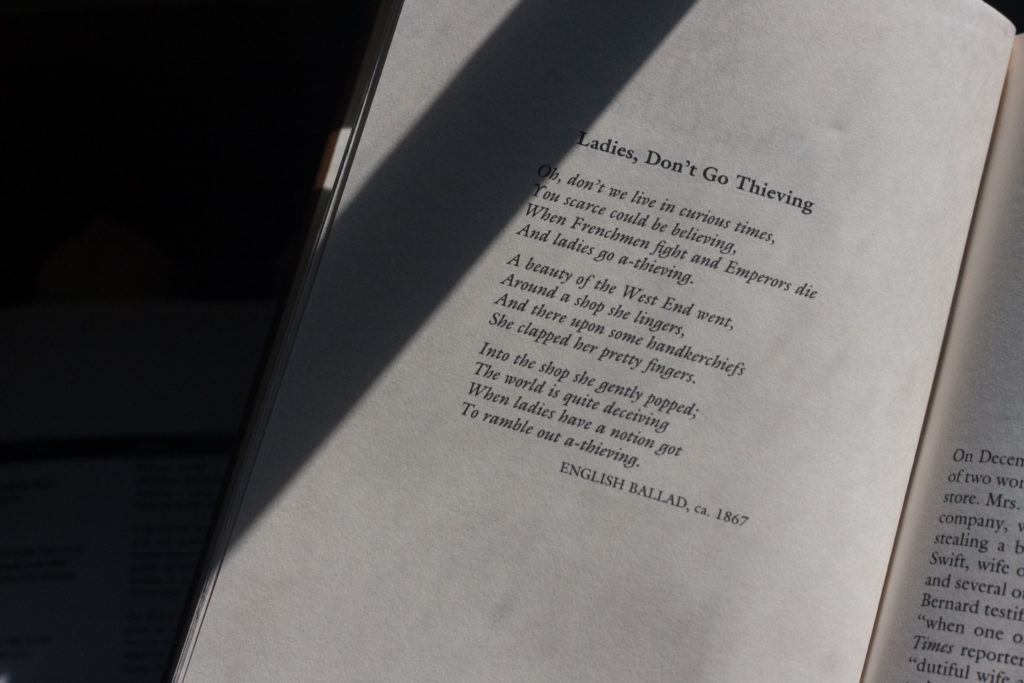

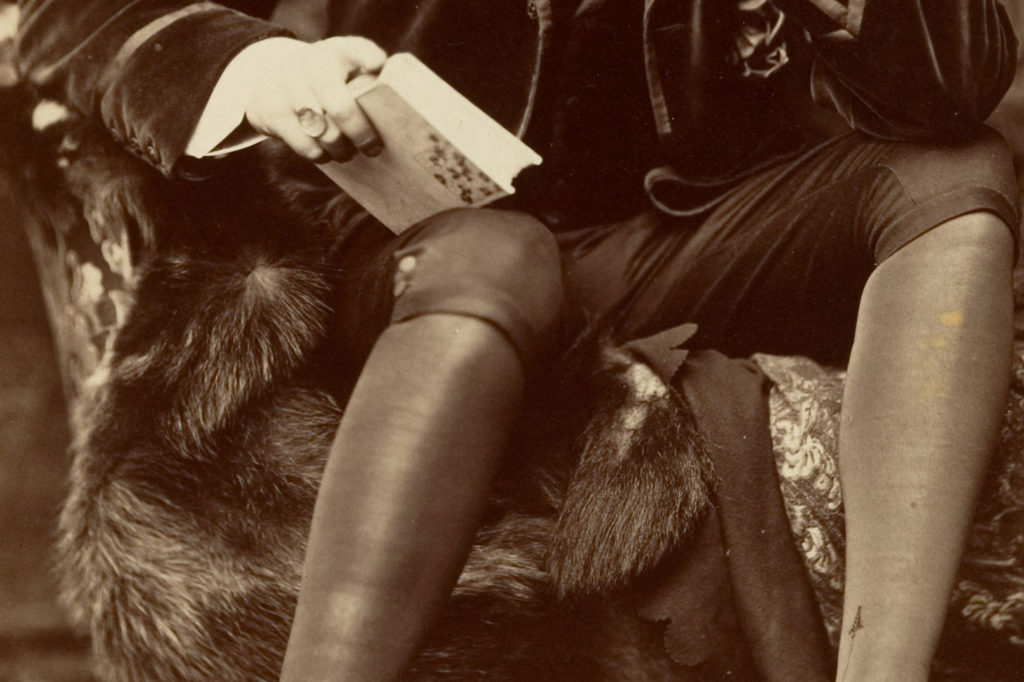

There is more than Sarony’s luxe eccentricity to mention, though: the article opens with a mention that the state legislature, under the thrall of Anthony Comstock’s anti-vice movement, was then entertaining the idea of a law to prohibit any representation of the nude human figure from going on display (and a catty aside that the law’s advocates were not simply seeking legislation, but “incidentally some notoriety for themselves.”).

Surely America’s most flamboyant celebrity photographer would have an opinion on the Comstock crusaders?

The key, he explained, was in portraying the nude as refined, innocent and graceful – free of seductive gazes or vulgar poses, presented as naturally as a flower in nature. Citing his own work, he explained: “I think my work proves that photography has aspects personal and individual apart from mechanical considerations. The camera and its appurtenances are, in the hands of an artist, the equivalent of the brush of the painter, the pencil of the draughtsman, and the needle of the etcher.”

He would know: the U.S. Supreme Court had told him so.