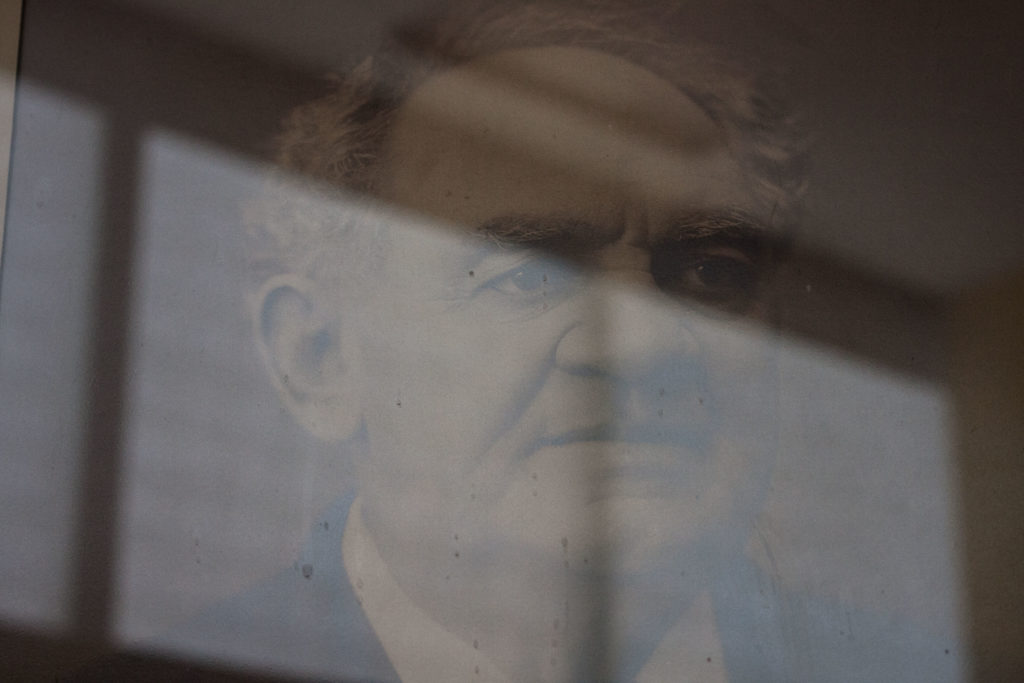

Have a drink with: Carl Hagenbeck

Ask him: But do you sing country ballads?

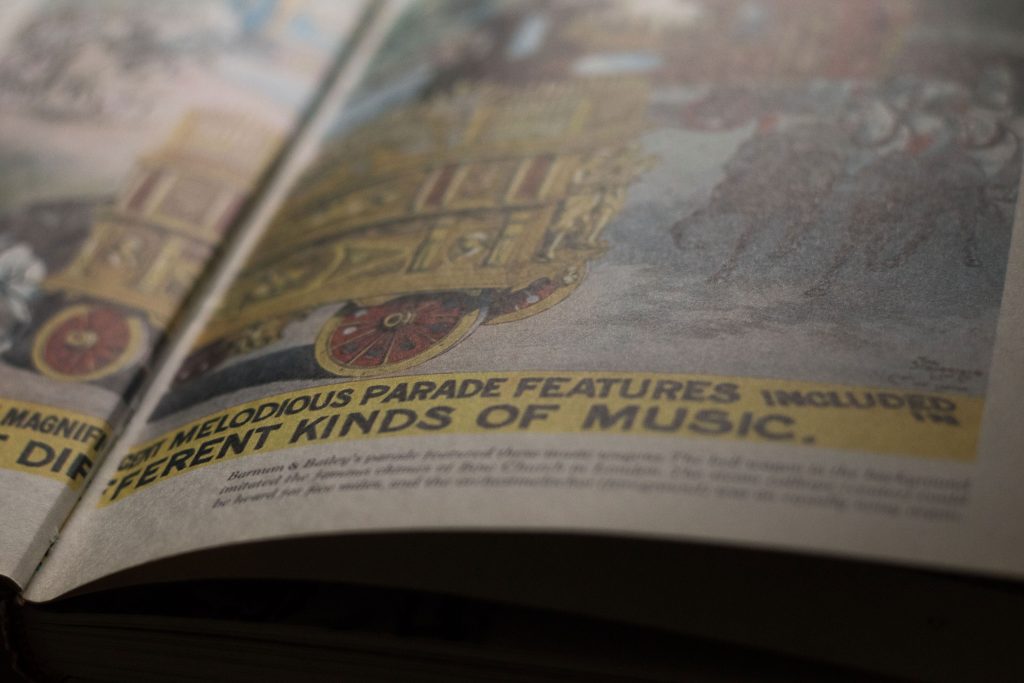

Like many other people, I spent the first chunk of my home confinement (thanks, coronavirus) plowing through Netflix’s hot documentary series “Tiger King” whilst eating an inordinate number of Girl Scout cookies. And the show is so relentlessly bananapants that it’s hard to believe that it could be a product of anything but the current moment in history. But no! The 19th century animal entertainment landscape also involved a cluster of larger-than-life figures jockeying for notoriety and revenue, and the birth of menageries in Western culture can tell us a lot about private zoos today.

There had certainly been exotic animals in the West going back far earlier, as part of private collections meant to demonstrate the owner’s status and ability. (Think Mike Tyson owning a tiger.) But where at the turn of the 19th century there were an isolated few animals in private hands, during the 1800s the menagerie emerged as a structured public entertainment. At first this was a matter of novelty: OMG COME SEE AN ELEPHANT. But as time went on, zoos had to embrace a sense of place in the world, and replaced brutal colonialism with an idea of moral purpose – the idea of participation in education, science and conservation.

Read on at Slate for my full take on Joe Exotic and his historical counterparts.