Have a drink with: Edwin Forrest & William Charles Macready

The play’s the thing…

Ask them about: Dead sheep as theater criticism

The New York Public Theater’s recent production of Julius Casear, in which the emperor bears a striking and not unintentional resemblance to Donald Trump, was hounded by controversy throughout its run. On June 16th, the performance was interrupted by protestors after Caesar’s assassination scene, with a right-wing activist climbing onstage to call attention to the “political violence” of the production.

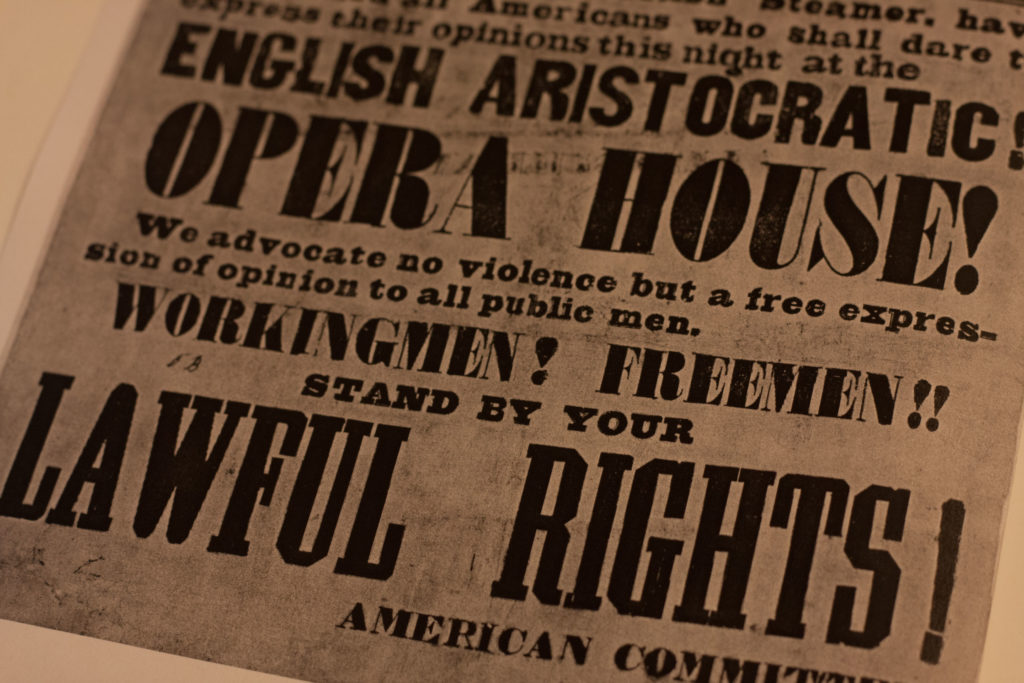

This is not the first time American theater – or American Shakespeare performance, for that matter – has been a forum for bitter fighting over contemporary politics. When actors rallied near Manhattan’s Astor Place in support of the Public Theater shortly after the contested performance, it was no doubt with some specific history in mind: namely, the Astor Place Riot of 1849, in which a nasty feud between Shakespearean actors led to an actual battle between New York’s elite and a burgeoning nativist movement.

The Astor Place Riot was New York’s deadliest day since the Revolution, and was set into motion by bad blood between the American actor Edwin Forrest and his British competitor William Charles Macready.

Forrest was a walking sack of Jacksonian masculinity. He had great hair, once ripped out a Shakespearean monologue while huffing nitrous oxide, and was incredibly tenacious, going so far as to draw out his divorce lawsuit for 18 years. He hissed his competitor Macready from the box seats during a performance – at the time, so rude as to be vulgar – and refused to apologize, complaining that Macready was desecrating Hamlet with wimpy dancing.

For his part, Macready was a classically trained, refined English actor who was a favorite of New York society types, and didn’t like cocksure upstarts hissing at him.

Their feud, highly publicized in the New York papers, was a sensational back-and-forth that came to symbolize class warfare in America. It went a little something like this:

British Actor: I am a classical Shakespearean actor.

American Actor: I have bitchin’ mutton chops, and I do awesome Shakespeare.

British Actor: Vulgar Yank.

American Actor: Aristocratic twat.

Regular Folks: Hey! British guy! You suck! The American guy does Shakespeare way better. We think it’s the chops. Get off the stage!

British Guy: Screw you guys, I’m going home.

Rich New Yorkers Including Washington Irving: Please stay and do Macbeth again? We’ll keep out the riffraff. The theater has a *dress code.*

British Guy: I shall perform the Scottish Play.

Regular Folks: BUY ALL THE TICKETS

Angry Mob: There are ten thousand of us and we’re upset about marginalization of the working class. Can we come too? And pitch rocks through the windows?

Regular Folks: Hang on. “Boo! Hiss! Out with you!”

NYPD: You, in the cheap seats: you’re headed to the theater jail.

Regular Folks: Wait, there’s a theater jail?

Angry Mob: Hello? We’ve still got rocks.

NYPD: help

National Guard: Everybody simmer down now.

Angry Mob: Or not?

National Guard: That’s it, we’re shooting people.

You can read about the Astor Place Riot, in more prosaic terms, in an essay I wrote for Smithsonian.

Fun Facts:

In the pre-Civil War era of the Five Points, moralism and outsize life were always butting up against each other. While upper-class folks tried to maintain a starched, dignified tradition, the reality was far livelier: “American theater had a reputation for condoning prostitution, liquor consumption and rude behavior and was not considered a respectable form of entertainment.” Different entertainers dealt with this in different fashion: some tried to stratify theater and retain its upper-class character; others, like P.T. Barnum, tried to remake theatrical entertainment as a respectable genre, through family-friendly temperance plays and moral drama.

Shakespeare really was the wild celebrity scene of its day – to wit, the infamous Booth family and their various shenanigans, which involved alcoholism, insanity (Junius Brutus Booth allegedly “saved himself from absolute mania by his extreme love for domestic retirement and agricultural pursuits”), Ford’s Theater, a mummy and an underrated modern play starring Frank Langella, which I saw on a junior high school field trip.

A discontented audience member in Cincinnati was so steamed at Macready, he chucked half a dead sheep onstage from the gallery during the mousetrap scene in Hamlet.*

In 1844, nativist voters swept the New York elections, leading to an urgent and diligent effort by Democrats and Whigs to flip those seats as soon as possible. The manifesto of the American Nativist party was “to extend the qualifying period for naturalization to twenty-one years, ban immigrants from public office, and campaign against foreign interference in public life.”*

Theater jail is real.

When he was older, Edwin Forrest traded his piled-up smolder for a Ron Swanson thing. Take a look.

Additional Reading:

Betsy Golden Kellem, “When New York City Rioted Over Hamlet Being Too British,” Smithsonian, July 19, 2017

* Nigel Cliff, The Shakespeare Riots: Revenge, Drama, and Death in Nineteenth-century America (2007)

Account of the terrific and fatal riot at the New-York Astor Place Opera House (1849)

James Rees, The life of Edwin Forrest: With reminiscences and personal recollections (1874)

William Toynbee, ed., The Diaries of William Charles Macready, 1833-1851, v.2 (1912)