Have a drink with: Abdul Karim

The jewel in the Crown

Ask him about: Royal language lessons

The movie Victoria and Abdul portrays the relationship between Queen Victoria and Abdul Karim, a young Indian man assigned to her service in the late 1880s. Karim, originally a clerk from Agra, India, came to Victoria’s service during her Golden Jubilee in 1887. He became a favorite friend and confidante, acting as the Queen’s Urdu language teacher and Indian secretary, much to the frustrated jealousy of the royal household.

Victoria had a complicated relationship with India: on the one hand, she was fascinated with and fetishized all things Indian – learning Urdu, bringing curries onto the regular dining rotation at the palace, and decorating an entire lavish chamber at her Osborne House with Indian arts and architecture (including a lavish portrait of Karim himself, alongside paintings of Indian craftspeople). On the other hand, the allure doesn’t change the fact that she was the ruler of a forcibly and uncomfortably subdued nation of people whose welfare wasn’t permitted to muddle the interior decorating. It’s hard to know for sure whether Abdul Karim was a proxy for Victoria’s general fascination with exotic India; a genuine friend who provided the added benefit of making her stiff-necked family crazy; a subservient target for the Queen’s romantic or maternal impulses; or something else entirely.

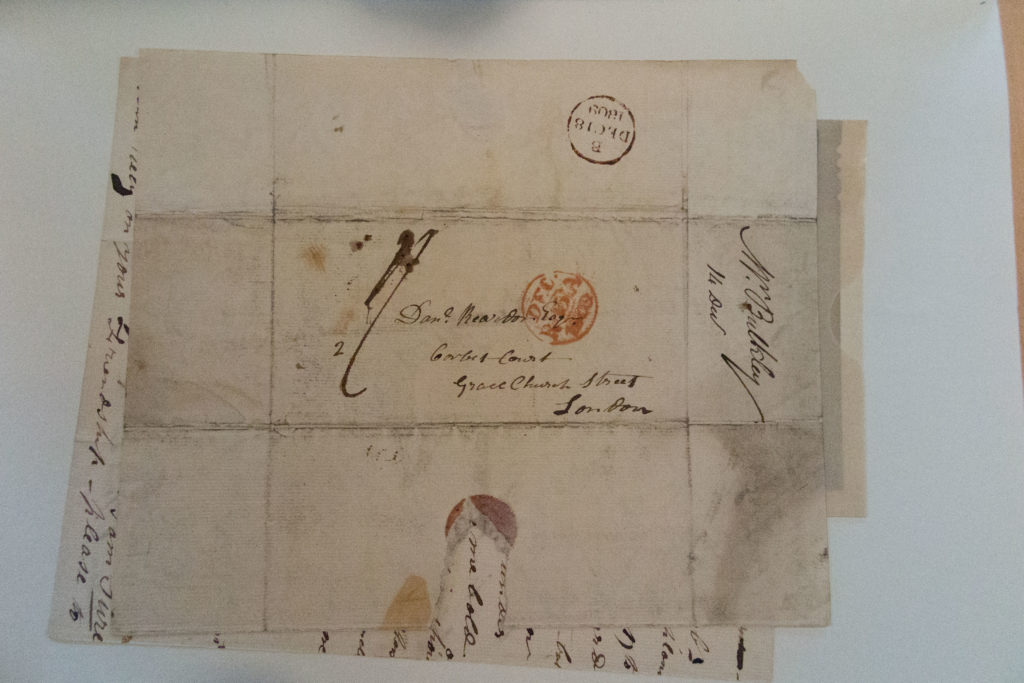

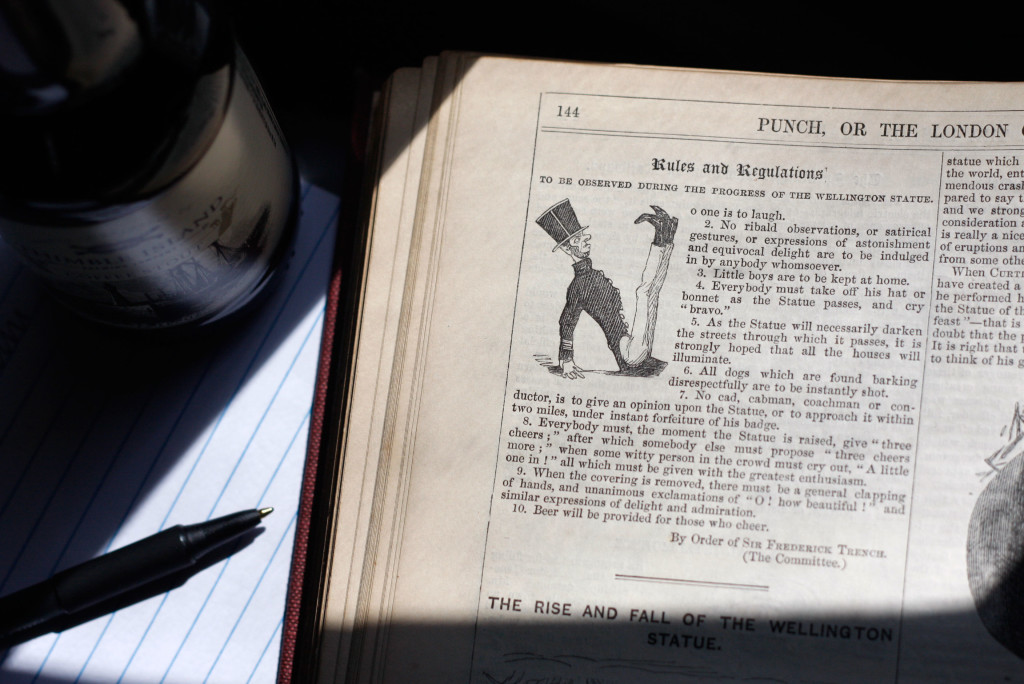

Nor is the movie the first time Western voices have been the ones to comment on Abdul Karim’s story, or his status as what writer Bilal Qureshi called “Manic Pixie Dream Brownie.” Karim was no stranger to news media at the time, and American papers particularly covered the fact of his employment with condescending, starchy amusement – like, look at the Queen learning the funny Eastern language! She has an Indian tutor! Just a few of the winning clippings: