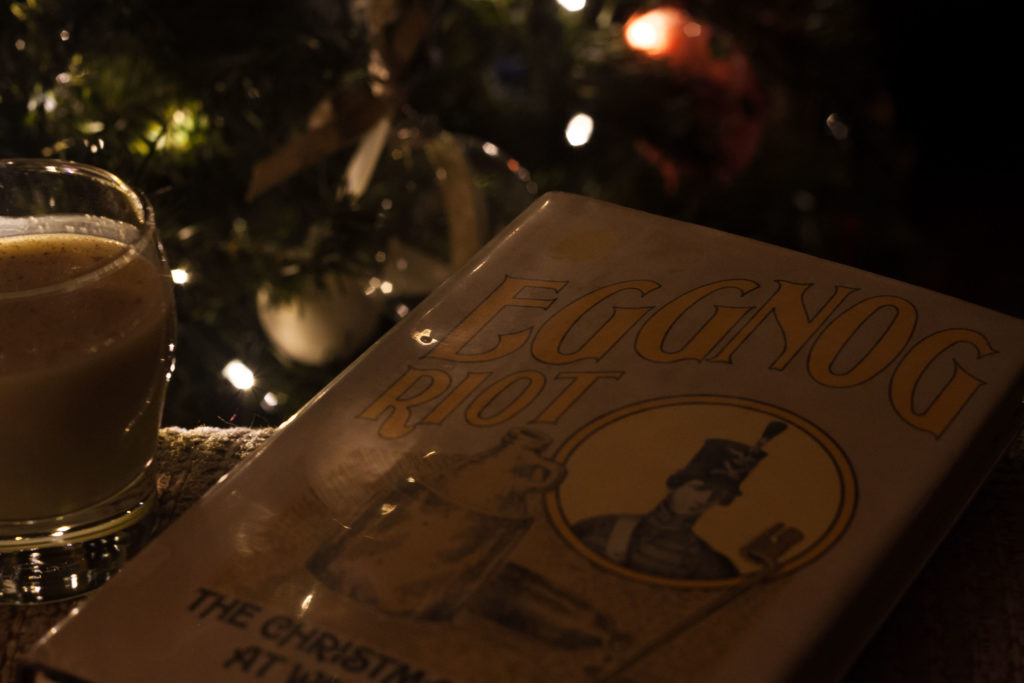

Have a drink with: Hugh Henry Brackenridge

Attorney, nog enthusiast, clothing optional

Ask him about: Pork as medicine

It’s the holiday season, and that means it’s time for nog.

Where did eggnog come from? If you look into it, you get a linguistic soup of suggestions (“nog” being an old word for strong ale, or “noggin” as a drinking vessel); and there are all sorts of historical links dragged out as to its origin, from medieval “posset” concoctions, to frothy egg-flips, to aristocratic milk punches (not clarified punches, which are an entirely different thing and which Ben Franklin loved). Consensus is that there is a centuries-long human history of making eggy milk drinks and pouring booze into them, which at some point syncretized into the modern concept of eggnog.

It doesn’t really matter. What does matter is that eggnog existed early on in American history, thanks to British culinary tradition and the good availability of eggs and dairy in the young nation, and it frequently involved a fair quantity of whatever liquor suited the local taste and economy.

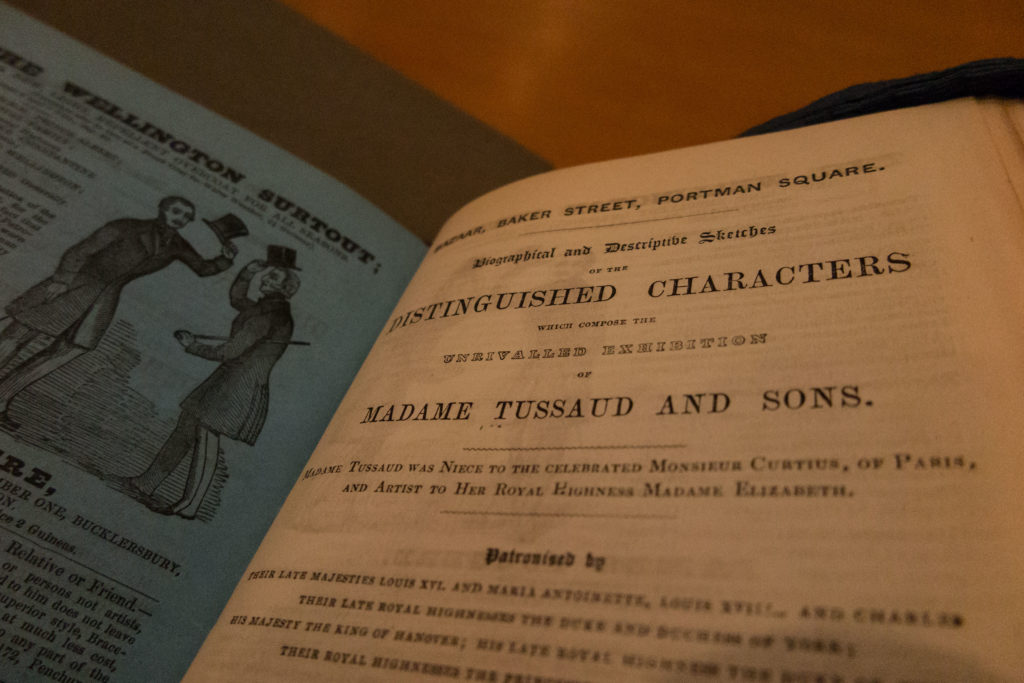

I say a “fair quantity.” We now turn to Judge Hugh Henry Brackenridge, a justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court at the turn of the 19th century, for demonstration of the fact that there is indeed such a concept as too much of a good thing.